Art for art s sake

Art for art s sake

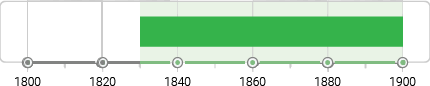

Victorian Era

From Georgian to Edwardian

Follow us

Art for Art’s Sake

In the early nineteenth century, French philosopher Victor Cousin coined a French slogan “l’art pour l’art”, which has the English meaning ‘Art for art’s sake’. Although writer Théophile Gautier did not use the exact words, he wrote in the preface of his novel ‘Mademoiselle de Maupin’ of 1835, the idea that art should be valued as art only. The artistic pursuits should have their own justification. This slogan became a bohemian slogan later on.

What is art for art’s sake movement in 19th Century?

The concept that art does not need any clarification or justification, that it does not need to serve any purpose, and that the beauty of the art itself is sensible enough for pursuing them was highly adopted by leading British and French writers and artists such as Oscar Wilde, Walter Pater, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. This group of artist pioneered a rebellious movement against Victorian moralism which is known as the Aesthetic Movement.

English Aesthetic Movement

The slogan ‘art for art’s sake’ is associated with this movement in history, which advocated that art should be kept separated from any social, political and economic influence. Famous Poet Edgar Allan Poe mentioned in his essay a very similar argument, ‘this poem written only for the poem’s sake’.

The slogan appeared in two works published simultaneously in 1868, one was in Pater’s review of William Morris’s Westminster Review and other in the Algernon Charles Swinburne’s William Blake. Walter pater mentioned in his most influential text of the Aesthetic Movement ‘Studies in the History of the Renaissance’ in 1873.

The writers and artists of the Aesthetic Movement advocated that there was no connection between morality and art. The art should provide refined sensuous pleasure, rather than convey a sentimental or moral message. The art should only show what the artist wants to show from the beauty of art.

Art and the Industrial Revolution

The slogan ‘art for art’s sake’ was a European social construct. It was largely a product of the Industrial Revolution. In most of the cultures from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, the artistic image was a religious practice. In medieval Europe, art was primarily used to decorate religious places and churches. Later the rise of the middle class initiated a demand for the ornamental art, portraits, illustrations, paintings, and landscapes for their home and offices. However, the industrial revolution created a void in the social structure where a large number of people had to leave in urban slums. This change of equation raised the question for the traditional value of the art and rejected romanticism.

During the same time, the academic painters felt a responsibility to improve society by presenting art, paint or images that reflect conservative moral values, such as Christian sentiments or virtuous behavior. However, the modernists rebelled against this thought and demanded the freedom to choose the style and subject of the art themselves. They felt that the religious and political institutions were influencing the artist’s work area and restricting individual artist’s liberty.

These progressive modernists challenged the conservative middle-class’s demand for art and adopted an antagonist attitude to stand at the forefront of the modern age of art and culture.

Latin Version and MGM Logo

The slogan is used commercially as well. The Latin meaning of the slogan ‘Art for art’s sake’ is “ARS GRATIA ARTIS’. This phrase is used by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, majorly known as MGM’s logo. The phrase is used as motto which appears in the logo of MGM behind the head of Leo the Lion.

Post-Modernism and Art for Art’s Sake

A failure of tradition was signified in the First World War and demonstrated that technological and scientific progress would not create a better world alone. This created a new cultural movement ‘Dadaism’ which declared that modernist art had rejected all prevailing artistic standard by imposing anti-art cultural work.

The concept of ‘art for art’s sake’ remained significant in a discussion about the importance of art and censorship. Art increasingly became a part of public life, in the form of film media, print media, and advertising. Later the art became a mechanical rather than manual art and lost the control of an individual artist.

However, as the modern era emerged, Art falls in the hands of civic institutions and government bodies. This institutions which have no ability to appreciate art themselves impose restrictions on artistic expression and limited the individual’s liberty to create the art to show the beauty of the art itself. In today’s world, the slogan becomes significant again where the art should be for art’s sake only.

Art for Art’s Sake

Summary of Art for Art’s Sake

Taken from the French, the term «l’art pour l’art,» (Art for Art’s Sake) expresses the idea that art has an inherent value independent of its subject-matter, or of any social, political, or ethical significance. By contrast, art should be judged purely on its own terms: according to whether or not it is beautiful, capable of inducing ecstasy or revery in the viewer through its formal qualities (its use of line, color, pattern, and so on). The concept became a rallying cry across nineteenth-century Britain and France, partly as a reaction against the stifling moralism of much academic art and wider society, with the writer Oscar Wilde perhaps its most famous champion. Although the phrase has been little used since the early twentieth century, its legacy lived on in many twentieth-century ideas concerning the autonomy of art, notably in various strains of formalism.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

The Important Artists and Works of Art for Art’s Sake

La Ghirlandata

A woman delicately plays a harp while two angels circle pensively above her head. The rich velvet of the woman’s green dress flows into the luxurious vegetation that surrounds her, her striking red hair echoed by the garland of flowers and the angels’ auburn locks. William Michael Rossetti, the brother of the artist, translated this work’s as «The Garlanded Lady» or «Lady of the Wreath,» with Alexa Wilding, the model depicted in the center of the work, portrayed as the ideal of love and beauty.

This is a painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a British artist associated with both Aestheticism and the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, and known for his tempestuous and often exploitative romantic relationships with female models and artists. This work’s title, along with the idealized treatment of subject matter, may be intended to evoke the spirit of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (c. 1503-19), then often known as La Giaconda («the happy one» or «the jocund one»), and revered by critics associated with Art for Art’s Sake such as Theophile Gautier and Walter Pater. In effect, Rossetti may have meant his idealized beauty to become an icon for the Aesthetic movement just as the Mona Lisa had become an icon of Renaissance art.

In its guide to the work, the Guildhall Art Gallery notes that the painting ushered in «a new aesthetic of painting,» as every element contributed to the elevation of beauty. William Michael Rossetti wrote that his brother’s intent was to «to indicate, more or less, youth, beauty, and the faculty for art worthy of a celestial audience, all shadowed by mortal doom.» In this respect, the painting summed up the «Cult of Beauty» for which the Pre-Raphaelites stood, and represents an important contribution to the principles of Art for Art’s Sake.

Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket

Artist: James Abbott McNeill Whistler

This iconic painting depicts a firework display at Cremorne Gardens in London. A few shadowy figures can be discerned in the foreground, depicting the shore of the Thames River, but most of the canvas is given over to the black night sky, lit up by the rocket’s falling gold sparks and the explosive smoke from the firework battery on the horizon. With its dreamy wash of color and abstracted figures, this painting represented the emergence of a new approach within painting which emphasized the artist’s freedom to represent a mood or emotion at the expense of representational accuracy.

No work is a better example of Whistler’s artistic stance. Perhaps for that reason, it became the subject of legal dispute after Whistler sued the noted critic John Ruskin for attacking the painting as worthless and poorly executed. While Whistler won the case, he received only a single farthing in settlement, and his legal fees contributed to his subsequent bankruptcy. Despite this Pyrrhic victory, Whistler’s defense played a key role in establishing the principles of art as an entirely liberated pursuit disconnected from all conventions of society, politics, or morality, which would be important to the development of modernism. Art critic James Jones notes that Whistler described a painting as «an arrangement of light, form and colour,» an emphasis which predicts, for example, the movement of Abstract Expressionism in the mid-twentieth century.

Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room

The concept of Art for Art’s Sake, via the Aesthetic movement, had a transformative effect on interior design and architecture. As art critic Fiona MacCarthy writes, «[o]ne of the main tenets of aestheticism was that art was not confined to painting and sculpture and the false values of the art market. Potential for art is everywhere around us, in our homes and public buildings, in the detail of the way we choose to live our lives.»

The Peacock Skirt

Aubrey Beardsley’s stylish ink sketch depicts the Biblical figure of Salome, whose failed seduction of John the Baptist leads to his beheading. Salome was the subject of Oscar Wilde’s eponymous one-act tragedy, written in French in 1891. When the English translation was published in 1894, it contained ten woodblock illustrations based on ink sketches by Beardsley, of which The Peacock Skirt is the second. Depicting the figure of Salome to the left in a long, elaborately patterned dress, with a peacock veil and headdress, the work embodies the qualities of elaborate beauty and luxury which Beardsley and other Art-for-Art’s-Sake artists promoted. At the same time, the sinister figure to the right, whose made-up face and feminine dress contrasts with their hairy legs, embraces the ideas of androgyny and sexual fluidity with which the movement was (often disapprovingly) associated.

The origins of Beardsley’s Salome series are in a single illustration depicting the anti-heroine kissing the severed head of John the Baptist, printed in 1893. Upon seeing the image, Wilde recognized an artistic affinity and invited Beardsley to illustrate the entire narrative. The illustration was heavily influenced by Whistler’s decorations for the peacock room, as well as the stylized lines of Japanese woodblock prints; the resultant long, sinuous depiction of bodies anticipates the work of Gustave Klimt and other Art Nouveau artists.

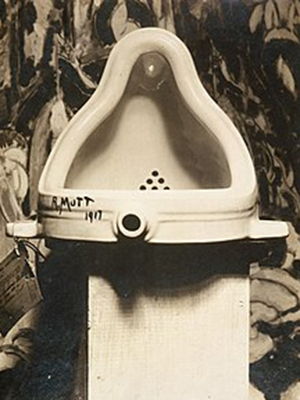

Fountain

Paradoxically, however, the work’s supporters did employ a version of the notion of Art for Art’s Sake to defend the object, arguing that Duchamp’s mere presentation the urinal imbued it with special significance, as an artwork which he had created. So, if the controversy demonstrated the fading importance of Art for Art’s Sake in the 20th century, it also showed the concept’s tenacity, as it became part of the foundation of modern art.

As contemporary art historian Peter Bürger wrote, «the autonomy of art is a category of bourgeois society. The relative dissociation of the work of art from the praxis of life in bourgeois society thus becomes transformed into the (erroneous) idea that the work of art is totally independent of society.» Bürger noted how «Duchamp’s provocation not only unmasks the art market where the signature means more than the quality of the work; it radically questions the very principle of art in bourgeois society according to which the individual is considered the creator of the work of art.»

Full Fathom Five

Full Fathom Five was among the first drip paintings Jackson Pollock completed. Its surface is clotted with an assortment of detritus, from cigarette butts to coins and a key. The uppermost layers were created by pouring lines of black and shiny silver house paint, though a large part of the paint’s crust was applied by brush and palette knife, creating an angular counterpoint to the weaving lines. Pollock’s drip paintings have been interpreted in numerous ways, some seeing them as inventing a new abstract language for the unconscious, others suggesting that they evoke the night sky, or in this case, the depths of the ocean.

In effect, while the idea of Art for Art’s Sake had nominally fallen out of fashion by the early twentieth century, it continued to inform trends in modern art, and its emphasis on the value of art as disconnected from all thematic concerns, became the grounds for Greenberg’s concepts of medium specificity, as well as his definition of the avant-garde and his arguments in favor of abstract art. As Lovatt adds, «[b]y emphasizing the opacity and autonomy of each ‘medium’, Greenberg disengaged the word from its relational and communicative connotations. Thus isolated, the modernist ‘medium’ was objectified and reified as a thing-in-itself, abstracted from the broader conditions of artistic production and reception.»

Beginnings

The Literary World and Théophile Gautier

Gautier had first studied painting before turning to literature and, subsequently, he became a leading art critic, so that he influenced both the literary and visual-art worlds. The poet Charles Baudelaire, a famous art critic in his own right, dedicated his groundbreaking poetry collection Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) to Gautier, whom he called «a perfect magician of French letters.» In 1862 Gautier was elected chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (National Society of Fine Arts) by a board that included Édouard Manet, Eugène Delacroix, and Gustave Doré among others. Gautier’s view that aesthetic beauty was central to the value of art, and that thematically suggestive or didactic work often lacked this quality, became widely influential in securing the reputation of the Aesthetic movement.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Whistler’s assertion that visual art should not promote any particular subject-matter led him to compare it to the purely abstract domain of music. With reference to his «nocturnes,» such as Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge (c. 1872-75), he described painting as «pure music,» noting that «Beethoven and the rest wrote music [. ] they constructed celestial harmonies [. ] pure music.»

In emphasizing the value of art for its own sake, Whistler helped to establish both the Aesthetic movement and Tonalism, the former movement having great currency in Britain, the latter in North America. In 1893, the critic George Moore, in his book Modern Painting, wrote that, «[m]ore than any other painter, Mr. Whistler’s influence has made itself felt on English art. More than any other man, Mr Whistler has helped to purge art of the vice of subject and belief that the mission of the artist is to copy nature.»

Aesthetic Movement

By 1860 the Aesthetic movement had emerged, coalescing around the influential idea of Art for Art’s Sake, with its base in the United Kingdom. Informed by Whistler’s pioneering work and Gautier’s criticism, the movement became associated particularly with images of female beauty set against the decadence of the classical world, as exemplified by the work of artists such as Albert Joseph Moore and Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

The canonical art critic Walter Pater became a leading proponent of Aestheticism. In his influential book The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry (1873) he stated that «art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality of your moments as they pass, and simply for these moments’ sake.» In so doing, he extended the concept of Art for Art’s Sake to define the kind of experience that a viewer should derive from a particular artwork, rather than merely applying it to the artist’s intentions.

Decadent Movement

The Decadent movement, which began in the 1880s, developed alongside the Aesthetic movement and shared roots in the mid-nineteenth, with Beardsley a significant figure in both schools. The Decadent movement, however, was particularly associated with France, notably with the work of the French-based Belgian artist Félicien Rops. Rops was a peer of Charles Baudelaire, who had proudly declared himself a «decadent» in his Les Fleurs du Mal («The Flowers of Evil») (1857), after which time the term became synonymous with a rejection of nineteenth-century banality, puritanism, and sentimentality. In 1886, the publication of the magazine Le Décadent in France gave the Decadent movement its name.

Tonalism

The art of Tonalism, mainly based in North America, held no truck with the scandal-seeking decadence of Beardsley and his peers. However, with their glowing, mist-filled, atmospheric landscapes, the Tonalists pioneered a style that was, in its own way, equally committed to the notion of Art for Art’s Sake.

Whistler was a lodestar for these artists. As the art historian David Adams Cleveland notes, Tonalism’s «emphasis on balanced design, subtle patterning, and a kind of otherworldly equipoise came directly out of the Aesthetic movement and the work and artistic philosophy of Art for Art’s Sake promoted by its greatest exponent, James McNeil Whistler.» In works such as Nocturne: The River at Battersea (1878), Whistler emphasized mood and atmosphere while exploring a simplified, almost abstract landscape in terms of its color tonalities.

Art critic Grace Glueck describes Tonalism as «not really a movement, but a mix of tendencies that began to drift together around 1870.» «[I]t remained a style without a name,» she adds, «until the mid-1890s.» Tonalism became a touchstone within US art, associated in particular with the North-American painters George Inness and Albert Pinkham Ryder, as well as the photographer Edward Steichen.

Whistler vs. Ruskin

Many of the principles of Art for Art’s Sake were publicly exclaimed by James Abbott McNeill Whistler during a famous libel case, which pitted his views against those of the Victorian art critic John Ruskin. The roots of the dispute were in the founding of the Grosvenor gallery in London in 1877. The gallery promoted the Aesthetic movement, and, as Fiona MacCarthy notes, became a «fashionable talking shop. The gallery’s proximity to the Royal Academy polarized opinion about the techniques and purposes of art.»

It was this polarization of opinion which led Ruskin, a proponent of more traditional technical and moral values within art, to dismiss Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875), shown in the first Grosvenor exhibition, as the equivalent of «flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.» Never shy of publicity, Whistler sued Ruskin for libel, and the case came to court in 1878.

During the legal proceedings, Ruskin used a portrait of Vincenzo Catena’s Portrait of the Doge, Andrea Gritti (1523-31), then thought to be painted by Titian, as an example of «real art» meant to counter Whistler’s painting. By arguing his right to freedom from pre-imposed artistic standards, Whistler won the case. However, he was awarded only a single farthing in damages, and his legal expenses and the public controversy which the episode had caused severely impacted on his career, to the extent that he was forced to declare bankruptcy, subsequently moving to Paris.

Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetic Movement Teapot

Following Whistler’s trial, the British public, as well as a number of powerful cultural figures, turned against the Aesthetic movement, and what they perceived as the indulgence and immorality of Art for Art’s Sake. In 1881, the English dramatist W.S. Gilbert premiered Patience, a musical satirizing the leading Aesthetes, while cartoons lampooning Aestheticism appeared frequently in Punch, the leading British magazine of satire and humor.

Oscar Wilde, by this time already an established writer and a cultural celebrity, was often the target for attacks with homophobic overtones. As the art historian Sally-Anne Huxtable writes, he was «the most famous Aesthete of them all [. ] at that time dressing in velvet breeches, lecturing on the topic of Art and supposedly quipping that he was ‘finding it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue and white china’.» In 1882, playing off the success of W.S. Gilbert’s Patience, which had included a character based on Wilde called Bunthorne, the designer James Hadley, employed at the famous Royal Worcester Porcelain Factory, created his so-called Aesthetic Movement Teapot.

This said, the artistic debate that Hadley alluded to, masked an uglier hostility towards the homosexual tendencies seen to be wrapped up in ideas of Art for Art’s Sake. Presenting a young man on one side and a young woman on the other, the teapot suggests the erosion of the traditional masculine and feminine qualities, encapsulating what Huxtable calls «the hysterical fears circulating in the 1880s about the effects that effeminacy and the blurring of gender roles might have on the future British population.» These fears placed figures like Wilde in the spotlight, and in 1895, after two trials and much public scandal, he was sentenced to prison and two years’ hard labor after being convicted of «gross indecency» for homosexual acts.

Concepts and Trends

Philosophy

The idea of aesthetic experience that informed Art for Art’s Sake arguably has its roots in the work of eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant, who held that the true appreciation of art was a process disconnected from all worldly concerns. Subsequent eighteenth- and nineteenth-century artists and thinkers, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and Thomas Carlyle, built upon Kant’s ideas. Schiller’s Briefe über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen (1795) («On the Aesthetic Education of Man»), inspired by Kant, developed the idea that appreciating art took the viewer away from social, political, or otherwise ‘non-artistic’ concerns: «beauty cajoles from [man] a delight in things for their own sake.» As a result, when Benjamin Constant first used the phrase «art for art’s sake» in 1804, he was coining a memorable phrase that captured an already important philosophical trend.

Art Criticism

A number of nineteenth-century art critics, particularly Théophile Gautier and Walter Pater, did much to establish the ideas of Art for Art’s Sake. Pater famously described the possession of an artistic sensibility as meaning «[t]o burn always with [a] hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life.» As art historian Rachel Gurstein writes, «[s]uch an elevated, if extravagant, ideal of art demanded a new kind of criticism that would match, and even surpass, the intensity of the impressions that a painting evoked in the sensitive viewer, and the aesthetic critic responded with ardent prose poems of his own.» She adds that «proper Victorians thought such a view of art and criticism immoral and irreligious. They were appalled by what they perceived as its decadence.»

Effect on Art History

With their passionate criticism, Gautier and Pater influenced the evaluation not just of contemporary art but also of the Renaissance and classical work that influenced it. Rejecting the story-telling style and moral subject-matter of classical history painting, exemplified by Raphael and favored by the traditional academies, these two critics rediscovered the work of artists such as Botticelli. Additionally, as Rochelle Gurstein writes of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (c. 1503-19), «[a]lthough many writers associated with the art-for-art’s sake movement in France and England paid enthusiastic tribute to the painting, Theophile Gautier and Walter Pater are now best known for launching it on its modern path to what is now inelegantly called ‘iconicity.'»

Opponents of Art for Art’s Sake

From the beginning, the idea that art should be judged solely on a set of isolated aesthetic or formal criteria was opposed by a range of creatives and thinkers. Academic painters rejected the work associated with Art for Art’s Sake as frivolous, lacking the moral purpose offered by the classical subjects which the Academy favored. Ruskin’s criticism of Whistler’s work encapsulates some aspects of this position.

Just as it was criticized by traditionalists, Art for Art’s Sake also gradually fell afoul of emerging avant-garde trends in the arts. Gustave Courbet, the pioneer of Realism, generally seen as the first modern art movement, consciously distanced his aesthetic approach from Art for Art’s Sake in 1854, while also rejecting the standards of the academy, presenting them as two sides of the same coin: «I was the sole judge of my painting [. ] I had practiced painting not in order to make Art for Art’s Sake, but rather to win my intellectual freedom.»

Courbet’s position anticipated that of many forward-thinking artists who felt, as the novelist George Sand wrote in 1872, that «Art for art’s sake is an empty phrase. Art for the sake of truth, art for the sake of the good and the beautiful, that is the faith I am searching for.» Modernism and Avant-Garde trends in art increasingly became associated not with a mere decadent rejection of academic and Victorian morals, but with the proposition of alternative social, political, and ethical ideals.

Later Developments

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, «[t]he Aesthetic project finally ended following the scandal of the trial, conviction and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde for homosexuality in 1895. The fall of Wilde effectively discredited the Aesthetic Movement with the general public, though many of its ideas and styles remained popular into the 20th century.» With the decline of the Aesthetic movement, the phrase «art for art’s sake» fell out of fashion, though it continued to exert a presence, often notably, in other countries.

In St. Petersburg in 1899 Sergei Diaghilev, along with Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois, founded the magazine Mir iskusstva («World of Art»). The magazine was allied with a group of young artists in St. Petersburg which had formed the World of Art movement the preceding year. Promoting Art for Art’s Sake and artistic individualism, the group had perhaps its greatest impact through the formation of the groundbreaking Ballets Russes, which Diaghilev founded in 1907, and which operated until 1927.

The idea of Art for Art’s Sake had a profound if somewhat paradoxical influence on avant-garde art. As art historian Doug Singsen notes, «the avant-garde was not simply a negation of l’art pour l’art but rather both a negation and continuation of it.» Many leading twentieth-century artists dismissed it. Pablo Picasso stated «[t]his idea of art for art’s sake is a hoax,» while Wassily Kandinsky wrote that «[t]his neglect of inner meanings, which is the life of colours, this vain squandering of artistic power is called ‘art for art’s sake.'» Nonetheless, the concept was often met with ambiguity. Kandinsky empathized with the concept to a limited extent, describing it as «an unconscious protest against materialism, against the demand that everything should have a use and practical value.»

The leading art critic Clement Greenberg, who promoted Abstract Expressionism in the post-World War II era, build his concepts of medium specificity and formalism upon the groundwork of Art for Art’s Sake. As art historian Anna Lovatt writes, «Greenberg expanded the concept of art’s autonomy as he developed his concept of medium specificity.» Contemporary art historian Paul Bürger described the concept of Art for Art’s Sake as fundamental to the evolution of the avant-garde and modernism in his influential 1974 text Theory of the Avant-Garde: «the autonomy of art is a category of bourgeois society. It permits the description of art’s detachment from the context of practical life as a historical development.»

Social historian Rochelle Gurstein notes that «Pater’s style was a harbinger of modernity.» His influence continued into the twentieth century, particularly among noted critics and writers. Contemporary critic Denis Donoghue describes Pater’s influence as «a shade or trace in virtually every writer of significance from [Gerard Manley] Hopkins and [Oscar] Wilde to [John] Ashbery.» During the era of postmodernism in literary studies, many critics also took an interest in Pater’s worldview as a precursor to modern ideas of «deconstruction.» In 1991, scholar Jonathan Loesberg argued in Aestheticism and Deconstruction: Pater, Derrida, and de Man that aestheticism and modern deconstruction produced similar forms of philosophical knowledge and political effect through a process of self-questioning or «self-resistance,» and through the internal critique and destabilization of hegemonic truths.

In 2011 the Victoria & Albert Museum held The Cult of Beauty exhibition on the aesthetic movement. As curator Stephen Calloway noted, «the idea of looking at an art movement where, consciously, beauty and quality are central ideas, seems to me extraordinarily timely,» suggesting that Art for Art’s Sake is an idea with ongoing currency in the information and opinion-saturated contemporary world.

‘art for art’s sake’

Смотреть что такое «‘art for art’s sake’» в других словарях:

art for art’s sake — a slogan translated from the French l art pour l art, which was coined in the early 19th century by the French philosopher Victor Cousin (Cousin, Victor). The phrase expresses the belief held by many writers and artists, especially those… … Universalium

art for art’s sake — Any of several points of view related to the possibility of art being independent of concerns that order other disciplines. The term is primarily used regarding artists and artwriters of the second half of the nineteenth century, especially… … Glossary of Art Terms

art for art’s sake — noun Art with no function, whose only purpose is beauty … Wiktionary

art for art’s sake — used to convey the idea that the chief or only aim of a work of art is the self expression of the individual artist who creates it … Useful english dictionary

Poetry for Poetry’s Sake — Poetry for Poetry’s Sake was an inaugural lecture given at Oxford University by the English literary scholar Andrew Cecil Bradley on June 5, 1901 and published the same year by Oxford at the Clarendon Press. The topic of the speech is the role of … Wikipedia

art for art’s sake — artistic movement justifying artistic creation that serves no social or political purpose … English contemporary dictionary

Raised on Rock/For Ol’ Times Sake — Raised On Rock Студийный альбом … Википедия

Art and Anarchy — is a collection of essays by Edgar Wind, a distinguished twentieth century iconologist, historian, and art theorist. In 1960, Wind gave several lectures for the BBC as part of the Reith Lectures series; these lectures were collected, revised, and … Wikipedia

Art for charity — refers to the convergence between art and charitable giving. Artists may produce works specifically to be sold for charity or creators or owners of artistic works might donate all or part of the proceeds of sale to a good cause. Such sales are… … Wikipedia

Art School Confidential (comics) — For the film see Art School Confidential (film) Art School Confidential is a four page black and white comic by Daniel Clowes. It originally appeared in issue #7 (November 1991) of Clowes comic book Eightball and was later reprinted in the book… … Wikipedia

art for arts sake

1 art

искусство;

Faculty of Arts отделение гуманитарных и математических наук

мастерство;

industrial (или mechanical, useful) arts ремесла

умение, мастерство, искусство;

military art военное искусство

фотографии разыскиваемых преступников

(обыкн. pl) хитрость;

he gained his ends by arts он хитростью достиг своей цели

attr. художественный;

art school художественное училище

is long, life is short посл. жизнь коротка, искусство вечно

attr. художественный;

art school художественное училище

вчт. иллюстративные вставки

искусство;

Faculty of Arts отделение гуманитарных и математических наук

and part in быть причастным (к чему-л.), быть соучастником (чего-л.)

(обыкн. pl) хитрость;

he gained his ends by arts он хитростью достиг своей цели

мастерство;

industrial (или mechanical, useful) arts ремесла

is long, life is short посл. жизнь коротка, искусство вечно

вчт. штриховая графика

умение, мастерство, искусство;

military art военное искусство

пат. ограничительная часть формулы изобретения prior

вчт. полутоновые иллюстрации

2 art

graphic art — графическое искусство, графика

environmental art — «пространственное искусство» (форма искусства, которая вовлекает зрителя в представление, выставку)

to practise an art — заниматься каким-л. видом искусства

Dance is an art. — Танец – это вид искусства.

Bachelor of Arts — бакалавр искусств (обладатель степени бакалавра по одной из гуманитарных или математических наук в университетах)

Work, in which they have taken a great deal of pains, and used a great deal of art. — Работа, которая принесла массу страданий, но в которую было вложено много мастерства.

He gained his ends by arts. — Он хитростью достиг своей цели.

to have / be art and part in smth. — быть причастным к чему-л., быть соучастником чего-л.

Art is long, life is short. — посл. Жизнь коротка, искусство вечно.

art film / movie — некоммерческий фильм

Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return. ( Bible) — Прах ты и в прах возвратишься. (Библия, книга Бытия, гл. 3, ст. 19)

3 искусство

а work of art;

драматическое

у do* smth. for its own sake.

См. также в других словарях:

Art and Anarchy — is a collection of essays by Edgar Wind, a distinguished twentieth century iconologist, historian, and art theorist. In 1960, Wind gave several lectures for the BBC as part of the Reith Lectures series; these lectures were collected, revised, and … Wikipedia

Culture for the Masses — The Goodies episode Episode no. Series 2 Episode 13 (of 76) Produced by Starring … Wikipedia

Culture for the Masses (Goodies episode) — Infobox The Goodies episode name = Culture for the Masses number = 13 airdate = 5 November, 1971 (Friday mdash; 10.10 p.m.) director = producer = guests = Julian Orchard as the Minister of culture Tommy Godfrey as the Auctioneer Ray Marlowe as… … Wikipedia

arts, East Asian — Introduction music and visual and performing arts of China, Korea, and Japan. The literatures of these countries are covered in the articles Chinese literature, Korean literature, and Japanese literature. Some studies of East Asia… … Universalium

Art — This article is about the general concept of Art. For the categories of different artistic disciplines, see The arts. For the arts that are visual in nature, see Visual arts. For people named Art, see Arthur (disambiguation). For other uses, see… … Wikipedia

Art and Revolution — BackgroundWagner had been an enthusiast for the 1848 revolutions and had been an active participant in the Dresden Revolution of 1849, as a consequence of which he was forced to live for many years in exile from Germany. Art and Revolution was… … Wikipedia

Art Renewal Center — The Art Renewal Center (ARC) is an organization led by Fred Ross dedicated to classical realism in art, as opposed to the Modernist developments of the 20th century. It exists primarily as an online art gallery.Edwards, Alun.… … Wikipedia

art — <<11>>art (adj.) produced with conscious artistry, as opposed to popular or folk, 1890, from ART (Cf. art) (n.), possibly from influence of Ger. kunstlied art song (Cf. art film, 1960; art rock, 1968). <<12>>art (n.) early 13c., skill as a result … Etymology dictionary

Art of Noise — Infobox musical artist Name = Art of Noise Img capt = Img size = Landscape = Background = group or band Alias = Origin = London, England Genre = Synthpop, Avant garde, Ambient, New Wave Years active = 1983 1990, 1998 2000 Label = ZTT China… … Wikipedia

Art Renewal Center — Le Art Renewal Center est une organisation américaine s intéressant au réalisme classique dans les arts, en opposition aux courants modernistes du XXe siècle. C est avant tout un Musée des Beaux Arts en ligne. Ce centre a été créé en 2000… … Wikipédia en Français

‘art for art’s sake’

1 art for art’s sake

2 art for art’s sake

3 ‘art for art’s sake’

4 sake

ради;

do it for Mary’s sake сделайте это ради Мэри;

for our sakes ради нас sake: for God’s

ради бога, ради всего святого (для выражения раздражения, досады, мольбы) ;

for conscience’ sake для успокоения совести sake: for God’s

ради бога, ради всего святого (для выражения раздражения, досады, мольбы) ;

for conscience’ sake для успокоения совести sake: for God’s

ради бога, ради всего святого (для выражения раздражения, досады, мольбы) ;

for conscience’ sake для успокоения совести for old

в память прошлого;

for the sake of glory ради славы for the

ради;

do it for Mary’s sake сделайте это ради Мэри;

for our sakes ради нас for the

ради;

do it for Mary’s sake сделайте это ради Мэри;

for our sakes ради нас for the

ради;

do it for Mary’s sake сделайте это ради Мэри;

for our sakes ради нас for old

в память прошлого;

for the sake of glory ради славы for the

of making money из-за денег;

sakes alive! амер. вот тебе раз!, ну и ну!;

вот это да! for the

of making money из-за денег;

sakes alive! амер. вот тебе раз!, ну и ну!;

вот это да!

5 sake

6 art

graphic art — графическое искусство, графика

environmental art — «пространственное искусство» (форма искусства, которая вовлекает зрителя в представление, выставку)

to practise an art — заниматься каким-л. видом искусства

Dance is an art. — Танец – это вид искусства.

Bachelor of Arts — бакалавр искусств (обладатель степени бакалавра по одной из гуманитарных или математических наук в университетах)

Work, in which they have taken a great deal of pains, and used a great deal of art. — Работа, которая принесла массу страданий, но в которую было вложено много мастерства.

He gained his ends by arts. — Он хитростью достиг своей цели.

to have / be art and part in smth. — быть причастным к чему-л., быть соучастником чего-л.

Art is long, life is short. — посл. Жизнь коротка, искусство вечно.

art film / movie — некоммерческий фильм

Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return. ( Bible) — Прах ты и в прах возвратишься. (Библия, книга Бытия, гл. 3, ст. 19)

7 art

искусство;

Faculty of Arts отделение гуманитарных и математических наук

мастерство;

industrial (или mechanical, useful) arts ремесла

умение, мастерство, искусство;

military art военное искусство

фотографии разыскиваемых преступников

(обыкн. pl) хитрость;

he gained his ends by arts он хитростью достиг своей цели

attr. художественный;

art school художественное училище

is long, life is short посл. жизнь коротка, искусство вечно

attr. художественный;

art school художественное училище

вчт. иллюстративные вставки

искусство;

Faculty of Arts отделение гуманитарных и математических наук

and part in быть причастным (к чему-л.), быть соучастником (чего-л.)

(обыкн. pl) хитрость;

he gained his ends by arts он хитростью достиг своей цели

мастерство;

industrial (или mechanical, useful) arts ремесла

is long, life is short посл. жизнь коротка, искусство вечно

вчт. штриховая графика

умение, мастерство, искусство;

military art военное искусство

пат. ограничительная часть формулы изобретения prior

вчт. полутоновые иллюстрации

8 искусство

а work of art;

драматическое

у do* smth. for its own sake.

9 an ivory tower

Throughout the nineteenth century we find the artist engaging in a vain effort to deny the world which imposes upon him standards he can never accept. Some do so by building their ivory tower and hoisting from its summit the silken banner of art for art’s sake. (R. Fox, ‘The Novel and the People’, ch. IV) — Мы видели, как в течение всего XIX века художники тщетно пытались отгородиться от мира, навязывающего им нормы, которые они не могут принять. Некоторые для этого уединялись в «башню из слоновой кости», вывешивая знамя искусства ради искусства.

10 интерес

к искусству interest in art;

в

ах in smb.`s interests;

это в ваших

be* of the utmost interest, be* of great interest.

См. также в других словарях:

art for art’s sake — a slogan translated from the French l art pour l art, which was coined in the early 19th century by the French philosopher Victor Cousin (Cousin, Victor). The phrase expresses the belief held by many writers and artists, especially those… … Universalium

art for art’s sake — Any of several points of view related to the possibility of art being independent of concerns that order other disciplines. The term is primarily used regarding artists and artwriters of the second half of the nineteenth century, especially… … Glossary of Art Terms

art for art’s sake — noun Art with no function, whose only purpose is beauty … Wiktionary

art for art’s sake — used to convey the idea that the chief or only aim of a work of art is the self expression of the individual artist who creates it … Useful english dictionary

Poetry for Poetry’s Sake — Poetry for Poetry’s Sake was an inaugural lecture given at Oxford University by the English literary scholar Andrew Cecil Bradley on June 5, 1901 and published the same year by Oxford at the Clarendon Press. The topic of the speech is the role of … Wikipedia

art for art’s sake — artistic movement justifying artistic creation that serves no social or political purpose … English contemporary dictionary

Raised on Rock/For Ol’ Times Sake — Raised On Rock Студийный альбом … Википедия

Art and Anarchy — is a collection of essays by Edgar Wind, a distinguished twentieth century iconologist, historian, and art theorist. In 1960, Wind gave several lectures for the BBC as part of the Reith Lectures series; these lectures were collected, revised, and … Wikipedia

Art for charity — refers to the convergence between art and charitable giving. Artists may produce works specifically to be sold for charity or creators or owners of artistic works might donate all or part of the proceeds of sale to a good cause. Such sales are… … Wikipedia

Art School Confidential (comics) — For the film see Art School Confidential (film) Art School Confidential is a four page black and white comic by Daniel Clowes. It originally appeared in issue #7 (November 1991) of Clowes comic book Eightball and was later reprinted in the book… … Wikipedia

art for art’s sake

Смотреть что такое «art for art’s sake» в других словарях:

art for art’s sake — a slogan translated from the French l art pour l art, which was coined in the early 19th century by the French philosopher Victor Cousin (Cousin, Victor). The phrase expresses the belief held by many writers and artists, especially those… … Universalium

art for art’s sake — Any of several points of view related to the possibility of art being independent of concerns that order other disciplines. The term is primarily used regarding artists and artwriters of the second half of the nineteenth century, especially… … Glossary of Art Terms

art for art’s sake — noun Art with no function, whose only purpose is beauty … Wiktionary

art for art’s sake — used to convey the idea that the chief or only aim of a work of art is the self expression of the individual artist who creates it … Useful english dictionary

Poetry for Poetry’s Sake — Poetry for Poetry’s Sake was an inaugural lecture given at Oxford University by the English literary scholar Andrew Cecil Bradley on June 5, 1901 and published the same year by Oxford at the Clarendon Press. The topic of the speech is the role of … Wikipedia

art for art’s sake — artistic movement justifying artistic creation that serves no social or political purpose … English contemporary dictionary

Raised on Rock/For Ol’ Times Sake — Raised On Rock Студийный альбом … Википедия

Art and Anarchy — is a collection of essays by Edgar Wind, a distinguished twentieth century iconologist, historian, and art theorist. In 1960, Wind gave several lectures for the BBC as part of the Reith Lectures series; these lectures were collected, revised, and … Wikipedia

Art for charity — refers to the convergence between art and charitable giving. Artists may produce works specifically to be sold for charity or creators or owners of artistic works might donate all or part of the proceeds of sale to a good cause. Such sales are… … Wikipedia

Art School Confidential (comics) — For the film see Art School Confidential (film) Art School Confidential is a four page black and white comic by Daniel Clowes. It originally appeared in issue #7 (November 1991) of Clowes comic book Eightball and was later reprinted in the book… … Wikipedia

На странице представлены текст и перевод с английского на русский язык песни «Art for Art’s Sake» из альбома «Clever Clogs» группы 10cc.

Текст песни

Gimme your body Gimme your mind Open your heart Pull down the blind Gimme your love gimme it all Gimme in the kitchen gimme in the hall Art for arts sake Money for Gods sake Art for Arts sake Money for Gods sake Gimme the readys Gimme the cash Gimme a bullet Gimme a smash Gimme a silver gimme a gold Make it a million for when I get old Art for arts sake Money for Gods sake Art for Arts sake Money for Gods sake Money talks so listen to it Money talks to me Anyone can understand it Money can’t be beat Oh no When you get down, down to the root Don’t give a damn don’t give a hoot Still gotta keep makin the loot Chauffeur driven Gotta make her quick as you can Give her lovin’ make you a man Get her in the palm of your hand Bread from Heaven

Перевод песни

Демонстрируйте свое тело Демонстрируйте свой ум Открой свое сердце Потяните вниз Дай мне всю свою любовь Подавать на кухне в зале Искусство ради искусства Деньги ради Бога Искусство ради искусства Деньги ради Бога Дайте мне Дайте деньги Дай мне пулю Дай мне Дай мне серебро, золото Сделать миллион, когда я старею Искусство ради искусства Деньги ради Бога Искусство ради искусства Деньги ради Бога Деньги разговаривают, так что слушай. Деньги разговаривают со мной. Каждый может понять. Деньги нельзя бить. О нет. Когда ты спускаешься, до корня Не наплевать, не кричите Все еще нужно держать добычу Управляемый шофером Надо сделать ее как можно быстрее Дай ей любовь, сделай тебя мужчиной Подними ее на ладони Хлеб с небес

For Art’s Sake

Браслет For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

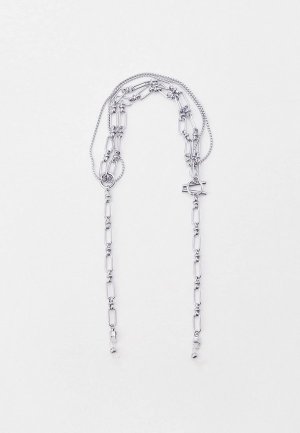

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Материал: металл. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Серьги For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: голубой. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: коричневый. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: черный. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: черный. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: зеленый. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: зеленый. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: черный. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: коричневый. Сезон: Осень-зима 2022/2023.

Браслет For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Колье For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой, прозрачный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Браслет For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Браслет For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепь For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Серьги For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Серьги For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Серьги For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Браслет For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Материал: металл. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепь For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой, розовый. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Материал: металл. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Материал: металл. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Материал: металл. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой, коричневый. Материал: металл, полимер. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой, черный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепь For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепочка для очков For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Колье For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой, мультиколор. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Колье For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Цепь For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой, белый. Сезон: Осень-зима 2021/2022.

Браслет For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Браслет For Art’s Sake. Цвет: белый, серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Браслет For Art’s Sake. Цвет: белый, золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Браслет For Art’s Sake. Цвет: белый, серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: черный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: коричневый. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: бордовый. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: черный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: серебряный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: мультиколор. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: коричневый. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: черный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: коричневый. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: зеленый. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: коричневый. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: белый. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: золотой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: черный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: голубой. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Очки солнцезащитные For Art’s Sake. Цвет: черный. Сезон: Весна-лето 2022.

Art For Art S Sake

Art For Art S Sake 10cc Live

10cc Art For Arts Sake

10cc Art For Art S Sake Later With Jools Holland BBC Two

Art For Arts Sake By 10cc REMASTERED VISUAL

10 CC Art For Art S Sake

10cc Art For Art S Sake Promo Clip

Art For Arts Sake By 10cc REMASTERED

10cc Art For Art S Sake Vinyl

10cc Art For Arts Sake 1975 Vinyl

Art For Art S Sake Live

10cc Art For Art S Sake Live In Scheveningen

10cc Art For Art S Sake 1976 Unique Extended Version

10CC Art For Art S Sake Live

Art For Art S Sake Single Edit

10cc Art For Art Sake 1982 Live Wembley Guitar Cover

10cc Art For Art S Sake Live 1975

10cc Art For Arts Sake

10cc Art For Arts Sake

Art For Art S Sake Live 1982

10cc Art For Art S Sake Live Sofiero Aug 10th 22

Art For Art S Sake 10cc

ART FOR ARTS SAKE 10CC 2015

10cc Art For Art S Sake

10cc Art For Art S Sake Director S Cut

10cc Art For Art S Sake

10CC Art For Art S Sake

Art For Art S Sake 10 CC Live

10cc I M Mandy Fly Me Art For Art S Sake Live In London 2007

10cc Art For Arts Sake

10cc Art For Art S Sake On Vinyl With Lyrics In Description

10cc Art For Art S Sake

10cc Art For Arts Sake

Art For Arts Sake 芸術こそ我が命 10cc Audio Only

10CC Art For Art S Sake Live May 2018

Art For Art S Sake 10cc

10CC Art For Art S Sake Live Ottawa Bluesfest 2012 07 14

10cc ART FOR ARTS SAKE BOOTIK MOOSIK

10CC Art For Arts Sake Live 2013

10cc Art For Arts Sake Fairfield Halls 2011

10cc Art For Arts Sake THE WOLF HUNTERZ Jon And Dolly Reaction

10 Cc ART FOR ART S SAKE BOOTIK MOOSIK

Art For Art Sake 10CC

10cc Art For Art S Sake Single Version

10CC ART FOR ARTS SAKE ON 7 INCH VINYL

Rory Smith Drumming Cover Art For Art S Sake By 10cc

The Truth Art For Art S Sake

10CC Art For Art S Sake Live Hvalstrandfestivalen 2017

10cc Art For Art S Sake

10cc Art For Art S Sake LIVE

Для вашего поискового запроса 10Cc Art For Art S Sake мы нашли 50 песен, соответствующие вашему запросу. Теперь мы рекомендуем загрузить первый результат Art For Art S Sake который загружен 10cc Topic размером 7.90 MB, длительностью 6 мин и битрейтом 192 Kbps.

Слушают сейчас

10Cc Art For Art S Sake

С Днем Рождения Любимый Повалий

Scotch Money Runner Original

Unut Beni Unuttugum Gibi Seni

The Jinx The Life And Deaths Of Robert Durst Trailer Official Hbo Uk

All Eyes Are On You Fnaf Speed Up

Куда Хуяришь Блять

Хуршид Расулов Отажон

Пародия На Шнурова От Однажды В России

Stranger Things Recap Jimmy Fallon On Yt

Новогодний Фитнес Микс

Uzmir Va Mira Qo Shiqlari

Salam Olsun Hüseynə

Ислам Итляшев Султан Лагучев Сборник Лучших Песен 2021

Желтые Розы Казаченко

Dschinghis Khan Moskau Bassboosted

Eddie Amador Do You

Ibuki Mioda From Me To You Too

Зульфия Чотчаева Буду Тебя Ждать

Diversant 13 Glamur I Pafos Remix By Zweifelhaft

Neon Genesis Evangelion Opening Ringtone For Ios Update

Uzeyir Mehdizade Heyatimiz Yeni Klip 2022

Safe And Sound Capital Cities Lyrics Remix Tiktok Song

Kokichi Version Mind Brand Male English Cover

Топ 10 Атмосферных Фонк Треков

Эльбрус Джанмирзоев Чародейка

Парень Из Торжка На Юбилее Надежды Бабкиной Надя Под Гармонь Театр Русская Песня

Jaloliddin Ahmadaliyev Ketsam Meni Topolmaysan Audio 2022

Клава Кока Бумеранг Премьера Клипа 2022

Eng Sara Qo Shiqlari To Plami 2022 Remix Yangi Uzbek Xit Qo Shiqlar 2022

Басы Пишите Песни С Басами Буду Делать

Доктор Ливси Самый Главный Оптимист

Мы В Школе Христа Фонограмма

Топ Шазам 2022 Самое Популярное Хиты 2022 Русская Музыка 2022 Лучшие Песни 2022

Яна Бир Бор Сочим Майда Уринг Ота Бахтимизга Доимо Сог Булинг Ота

Copyright ©Mp3crown.cc 2019

Все права защищены

На нашем музыкальном сайте вы можете бесплатно прослушать и скачать любимые, новые и популярные mp3 песни в хорошем качестве. Быстрый поиск любой композиции!

Почта для жалоб и предложений: [email protected]

art for art’s sake

Смотреть что такое «art for art’s sake» в других словарях:

art for art’s sake — a slogan translated from the French l art pour l art, which was coined in the early 19th century by the French philosopher Victor Cousin (Cousin, Victor). The phrase expresses the belief held by many writers and artists, especially those… … Universalium

art for art’s sake — Any of several points of view related to the possibility of art being independent of concerns that order other disciplines. The term is primarily used regarding artists and artwriters of the second half of the nineteenth century, especially… … Glossary of Art Terms

art for art’s sake — noun Art with no function, whose only purpose is beauty … Wiktionary

art for art’s sake — used to convey the idea that the chief or only aim of a work of art is the self expression of the individual artist who creates it … Useful english dictionary

Poetry for Poetry’s Sake — Poetry for Poetry’s Sake was an inaugural lecture given at Oxford University by the English literary scholar Andrew Cecil Bradley on June 5, 1901 and published the same year by Oxford at the Clarendon Press. The topic of the speech is the role of … Wikipedia

art for art’s sake — artistic movement justifying artistic creation that serves no social or political purpose … English contemporary dictionary

Raised on Rock/For Ol’ Times Sake — Raised On Rock Студийный альбом … Википедия

Art and Anarchy — is a collection of essays by Edgar Wind, a distinguished twentieth century iconologist, historian, and art theorist. In 1960, Wind gave several lectures for the BBC as part of the Reith Lectures series; these lectures were collected, revised, and … Wikipedia

Art for charity — refers to the convergence between art and charitable giving. Artists may produce works specifically to be sold for charity or creators or owners of artistic works might donate all or part of the proceeds of sale to a good cause. Such sales are… … Wikipedia

Art School Confidential (comics) — For the film see Art School Confidential (film) Art School Confidential is a four page black and white comic by Daniel Clowes. It originally appeared in issue #7 (November 1991) of Clowes comic book Eightball and was later reprinted in the book… … Wikipedia

Art for art s sake

The phrase “art for art’s sake” expresses both a battle

cry and a creed; it is an appeal to emotion as well

as to mind. Time after time, when artists have felt

themselves threatened from one direction or another,

and have had to justify themselves and their activities,

they have done this by insisting that art serves no

ulterior purposes but is purely an end in itself. When

asked what art is good for, in the sense of what utility

it has, they have replied that art is not something to

be used as a means to something else, but simply to

be accepted and enjoyed on its own terms.

The explicit and purposive assertion of art for art’s

sake is a strictly modern phenomenon. The phrase itself

begins to appear only in the early years of the nine-

teenth century, and it is some time after that before

a recognizable meaning and intention can be said to

emerge. This is quite as would be expected. For before

there can be any need and reason to assert that artistic

activity is self-sufficient and works of art are ends in

themselves, a certain intellectual and cultural climate

must occur. The essential catalyzing agent in this

process can be identified in a few words: it consists

in the tendency of the human career toward com-

plexity, specialization, and fragmentation. So long as

the structure of life—individual and social, economic

and functional, theoretical and practical—is relatively

compact and cohesive, there is little occasion for the

emergence of private groups with a strong sense of

their own interests and tasks as opposed to those of

other groups. Men had obviously all along filled differ-

ent roles requiring different skills and directed toward

different purposes; and their respective duties, respon-

sibilities, and powers had varied across a wide spec-

trum. But both the actual structure of society and the

attitude of men towards society, were largely holistic

and organismic. Consequently, the pursuits that we

now distinguish quite sharply, such as religion, moral-

ity, politics, law, science, technology, art, etc., were

not formerly regarded or practiced in such a separatist

manner. The same individuals were often engaged in

several of these activities, which were viewed as as-

pects of a single undertaking rather than as distinct

endeavors. Though men had certainly practiced art,

they had not, with certain exceptions, been highly

conscious of themselves as artists.

Beginning with the Renaissance, this cohesive cul-

tural and intellectual unity starts to crumble, and the

end of the eighteenth century sees it thoroughly disin-

tegrated. By then, divergent and divisive tendencies

are at work throughout the social fabric, finding ex-

pression in what we call the religious, political, scien-

tific, and industrial revolutions. Men’s newly awakened

interests contrast with their old habits and commit-

ments. Inspired by an intense dedication to specific

values and purposes, they are drawn together into

various groups, each with a strong sense of its own

identity and mission. As the result of this broad social

and cultural movement, men begin to think of them-

selves as scientists, ministers, politicians, financiers, or

artists; and they assert that as such they have a function

of particular importance and so require particular

privileges.

The more precise intellectual matrix of the doctrine

of art for art’s sake can most plausibly be located in

the philosophical system of Immanuel Kant, though

it must at once be added that Kant certainly did not

intend this outcome and would have repudiated it

vehemently. But he still made it possible and even

inevitable. Through the three Critiques, of Pure Rea-

son, Practical Reason, and Judgment, Kant established

a triadic division of man’s mental capacities and func-

tions. To paraphrase somewhat loosely Kant’s formida-

ble terminology, man is endowed with understanding

or cognition, with a sense of duty or conscience, and

with aesthetic taste or sensibility. Kant’s interest was

focused on the first two of these; he was anxious to

place science and morality on a firm foundation, and

so to avoid the drift toward relativism and skepticism

that had reached a climax in the work of Hume. The

third Critique, that of Judgment, plays a more ancillary

role, with its significance deriving from architectonic

considerations rather than from the intrinsic interest

of its subject matter.

Even if this was true of Kant, and the question is

highly debatable, it was certainly not true of his imme-

diate converts and followers in German Idealism. For

what Kant had done was establish the aesthetic as an

autonomous domain, coordinate with man’s cognitive

and moral faculties and playing a distinct role of its

own in the life of the mind. The Idealists were quick

to see the possibilities that this schema offered them.

Revolting more or less consciously against Rationalist

tradition, with its emphasis upon balance and propor-

tion, its insistence upon strict adherence to rules of

composition, its exaltation of reason and science, and

its morality of detachment and calculation, the Ro-

mantics were anxious to find a way to escape from

the confinement of this creed and to justify those other

aspects of human nature and existence that rationalists

neglected or denigrated.

Friedrich Schiller was the first to exploit Kant’s

doctrine of the aesthetic for this purpose. But he was

followed in rapid succession by Friedrich Schelling,

Hegel, and Schopenhauer; and then, at only a slight

remove, by the wave of Romanticism that swept over

France and England as well as Germany, propelled on

First, and more generally, there was the common

conviction that art played a serious and significant role

in life, that it exercised a human faculty that nothing

else could touch, and that it made a unique contri-

bution to man’s understanding of the world. Before this,

the value of works of art had been primarily regarded

as either utilitarian or ornamental; art was thought of

as a subsidiary and derivative phenomenon. Now the

aesthetic life was raised to a position of high dignity

and importance. Second, and more specifically, art was

now defined by reference to a particular human faculty

and need that brought it into being. Interpretations

of this aesthetic source varied, but it was always local-

ized in the sensuous, emotional, and perceptual aspect

of man’s nature. It was held that artists grasped reality

in an immediate and intuitive manner, embodied it in

a material form, and so made it available to direct

apprehension. In short, art yields concrete insight into

the reality that reason can present only in the guise

of abstract concepts.

The stage was thus set for the appearance of the

idea of art for art’s sake. But its actual entrance still

required two further developments. Artists had to ac-

quire a strong sense of their identity as artists, of the

intrinsic significance of the art they created, and of

their need to create freely without interference and

harassment. And other established social groups and

institutions had to become afraid of the threat that such

free artistic expression might pose to their conventional

values, beliefs, and practices. Once these conditions

existed, censorship, though already widely imposed on

literature since the Renaissance, was now directed

against many forms of art, both by the church and the

state, in an effort to control and direct art, or keep it

subservient to special uses and standards. Artists replied

by asserting that art was an end in itself, to be created

and judged in terms of purely aesthetic criteria.

The idea of art for art’s sake is thus to be seen as

partly a declaration of artistic independence and partly

an expression of the alienation of the artist from soci-

ety. It is at once a claim and a complaint. Insofar as

artists are men, their rejection by society causes them

to suffer psychically as well as economically; insofar

as they are artists, they glory in it as a proof of their

uniqueness. So the alienation that the artist expresses

when he dedicates himself to art for art’s sake is a

compound of protest and pride. In this guise, the idea

serves chiefly to sustain the artist’s ego.

As a declaration of artistic independence, the idea

plays a far more significant and constructive role. For

here it becomes a device by which artists justify them-

selves in the paths they follow and protect their work

against attack from an outraged society. So the history

of art for art’s sake is essentially a history of the various

attempts that are made to subvert art, as the artists

envisage it, by subordinating art to other purposes and

demands; the idea takes shape gradually and errati-

cally, as the threat comes now from one quarter now

from another. Although there is very little continuity

and development to be found in this history, it can

be seen as containing four major chapters, each con-

sisting of a counterattack against a different enemy.

These enemies can be conveniently labeled as conven-

tional morality and religion, utility and didacticism,

science, and subject matter.

Apparently the first to use the phrase L’art pour l’art

was Benjamin Constant in an entry in his Journal intime

for February 11, 1804. It is introduced quite casually

to refer to the aesthetic doctrines of Kant and Schell-

ing, which Constant finds “very ingenious.” The idea

then occurs with increasing frequency in the writings

of the Romantics and of all those who, like the Roman-

tics, felt the special calling of the artist and the aliena-

tion and lack of understanding under which artists

suffered: this list would include particularly Baudelaire,

Gautier, Hugo, Flaubert, and Mallarmé in France;

Whistler, Pater, and Oscar Wilde in England. In the

course of time, the phrase accretes around itself a large

but miscellaneous body of passions, convictions, com-

mitments, complaints, and especially antipathies.

In accord with the pattern suggested above, these

artistic attitudes and purposes can be seen as clustered

around four poles. Artists inveigh against conventional

bourgeois morality, with its prudery and hypocrisy, and

against all of the measures through which the govern-

ment, the church, and the press seek to impose this

morality and suppress any deviations from it. They

repudiate with equal vehemence and scorn the spirit

of utility, which asks of everything what practical

purpose it serves and is incapable of accepting and

enjoying anything as simply good in itself. In a similar

vein, they reject the claims of didacticism, refusing to

acknowledge that their art should proclaim any moral

truths or lessons. Artists also express an intense anxiety

about the inroads of science and the spread of the

scientific mentality, with its emphasis on material

things and mechanical processes, and its worship of

brute facts. Finally, artists reproach the sentimentality

of the public, which looks not at their works of art

but merely at the objects, scenes, and events that these

depict; that is, they resent the slavery of subject matter.

The tone and content of these complaints can best

People have acquired the habit of looking, as who should

say, not at a picture, but through it, at some human fact,

that shall, or shall not, from a social point of view, better

their mental or moral state. Alas! Ladies and gentlemen,

Art has been maligned. She has nought in common with

such practices. Purposing in no way to better others,

. having no desire to teach. Nature contains the

elements, in colour and form, of all pictures, as the keyboard

contains the notes of all music. To say to the painter,

that Nature is to be taken as she is, is to say to the player,

that he may sit on the piano

Théophile Gautier urges a similar doctrine, insisting

particularly upon the necessity for an absolute divorce

between man’s artistic and practical pursuits. His

argument is brief and pointed: “Only those things that

are altogether useless can be truly beautiful; anything

that is useful is ugly, for it is the expression of some

need, and the needs of man are base and disgusting, as

his nature is weak and poor” (Gautier [1834], p. 22).

Walter Pater puts the case in a more philosophical

way, seeking not only to extol art but also to explain

and justify its preeminent importance. His argument

rests upon the contrast between the richness and fleet-

ingness of immediate experience and the bare abstract

concepts to which analytical thought seeks to reduce

it. And he insists that the entire meaning and value

of life reside in the wealth and intensity of experiences.

The highest wisdom lies in explaining things, much less

in using them, but simply in sensing and feeling them.

He concludes in these terms: “Of such wisdom, the

poetic passion, the desire of beauty, the love of art

for its own sake, has most. For art comes to you pro-

posing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality

of your moments as they pass, and simply for these

moments’ sake” (Pater [1873], pp. 238-39).

In the twentieth century the idea of art for art’s sake

undergoes a rather radical transformation, generating

a more serious and systematic doctrine, and exerting

a more positive influence upon artistic creation. It now

appears in new interpretations of such concepts as

“pure poetry,” “significant form,” “plastic form.” The

significance of this movement lies in the insistence that

the work of art is an autonomous and self-contained

entity; its meaning and value are exhaustively con-

tained in its material and formal being. Works of art

do not need to borrow significance from biographical,

psychological, historical, or sociological sources; their

significance lies in the formal structures that they real-

ize in a material medium. These ideas had already

found eloquent expression as early as 1854 in Eduard

Hanslick’s book, The Beautiful in Music; they were

forcefully restated for the context of literature by

A. C. Bradley in his Oxford Lectures on Poetry (1909);

they received their most incisive advocacy in Clive

Bell’s Art (1919) and Roger Fry’s Vision and Design

(1920). Since then, this doctrine has become a com-

monplace of artistic creation and criticism, and has

served as the theoretical source and justification of

such important—and divergent—contemporary devel-

opments as those of abstract, nonobjective, non-

representational, and constructivist art, as well as

Dada, Surrealism, and Cubism.

So the idea of art for art’s sake has now ceased to

be an instrument of protest and defense, and has be-

come one of the central tenets of official aesthetic

dogma. It is not he who does or praises art for art’s

sake who must justify himself, but rather he who would

assign to art any values, or judge art by any standards,

other than those that are intrinsic to it. Yet the ad-

herents of art for art’s sake seem to be as uneasy in

their new security as they were in their former aliena-

tion. At the same time that they proclaim the auton-

omy of the artist and his art, their freedom from any

extrinsic purpose or obligation, they also insist that the

artist is a seer and a prophet, and that through his art

he makes available both a truth and a mode of existence

that are essential to human well-being. The most star-

tling illustration of this ambivalence occurs in Clive

Bell’s Art, where, within the brief span of forty pages,

Bell first urges a rigid doctrine of pure art and then

proclaims that art makes us aware “of the God in

everything, of the universal in the particular, of the

all-pervading rhythm” (Bell [1914], p. 54). But similar

conflicts of intention crop up on virtually every occa-

sion when contemporary artists write about their art.

The truth of the matter seems to be that the idea

of art for art’s sake is one of that numerous class of

important half-truths whose validity and vitality are

dependent upon the effective presence of their com-

plementary half-truths. This idea is necessary to pre-

serve the independence of the artist and the integrity

of the artistic enterprise. But its other half, which is

the idea of art for life’s sake, is equally necessary to

guarantee the integration of the artist into his society

and hence the meaningfulness of his art.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albert C. Barnes, The Art in Painting, 2nd ed. (New York,

1928). Monroe C. Beardsley, Aesthetics from Classical

Greece to the Present (New York, 1966). Clive Bell, Art

(London, 1914). A. C. Bradley, Oxford Lectures on Poetry

(Oxford, 1909). Albert Cassagne, La Théorie de l’art pour

l’art en France (Paris, 1906). Rose Egan, The Genesis of the

Theory of Art for Art’s Sake (Northampton, 1921; 1924).

Roger Fry, Vision and Design (London, 1920). Théophile

Gautier, Mademoiselle de Maupin (Paris, 1834). Edmund

Gurney, The Power of Sound (London, 1880). Eduard

Hanslick, The Beautiful in Music (London, 1891). Hilaire

Hiler, Why Abstract? (New York, 1945). José Ortega y

Gasset, The Dehumanization of Art (Princeton, 1948).

Walter Pater, The Renaissance (Oxford, 1873). Louise

Rosenblatt, L’Idée de l’art pour l’art dans la littérature

anglaise pendant la période victorienne (Paris, 1931). Irving

Singer, “The Aesthetics of ‘Art for Art’s Sake,’” JAAC, 12,

3 (1954), 343-59. James A. McNeill Whistler, The Gentle

Art of Making Enemies (London, 1890). John Wilcox, “The

Beginnings of L’art pour l’art,” JAAC, 11 (1953), 860-77.

[See also Romanticism in Literature; Romanticism

in Post-Kantian Philosophy.]

Art for art s sake

2. Art for Art’s Sake